It’s nearly five pm on Saturday April 1, 2017, and a crowd of more than three thousand people has gathered on Main Mall at UBC to help raise the Reconciliation Pole, a monument to the survivors of Canada’s residential schools.

Community members help raise Reconciliation Pole on April 1. 2017. (Photo Paul Joseph, UBC Communications and Marketing)

“Michael, ease off a little there,” yells MC Gordie Russ. “Buddy, pull some more. Gently now. Take up the slack.”

It’s nearly five pm on Saturday, April 1 2017, and a crowd of more than three thousand people has gathered on Main Mall at UBC to help raise the Reconciliation Pole, a monument to the survivors of Canada’s residential schools. After hours of emotional speeches by Indigenous leaders and residential school survivors, hundreds of people have taken hold of five main ropes and begun to pull the massive pole skywards, under the close supervision of five rope directors and MC Russ.

“Steady now,” Russ cries as the 17-metre pole finally stands upright, still wobbling slightly from side to side.

Then sunlight glints off the eagle on top, and the crowd lets out a huge cheer.

The raising was a cathartic moment for Haida master carver and hereditary chief ˀidansuu (Edenshaw), James Hart, who had been working on the pole for more than two years, with a team of assistants.

ˀidansuu (Edenshaw), James Hart dances during the ceremony on April 10, 2017. (Photo Paul Joseph, UBC Communications and Marketing)

“It’s for the Rest of the Country”

“I hope people get the meaning of it,” Hart says. “We know [about residential school], but it’s for the rest of the country.”

Hart was lucky, he says — he didn’t go to residential school, though his grandfather, great uncles and many other relatives and friends did.

Nearly 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to leave their families and attend residential schools between 1883 and 1996. In its 2015 report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) called the program “cultural genocide.”

Copper nails represent the children who died at residential schools. (Photo Paul Joseph, UBC Communications and Marketing)

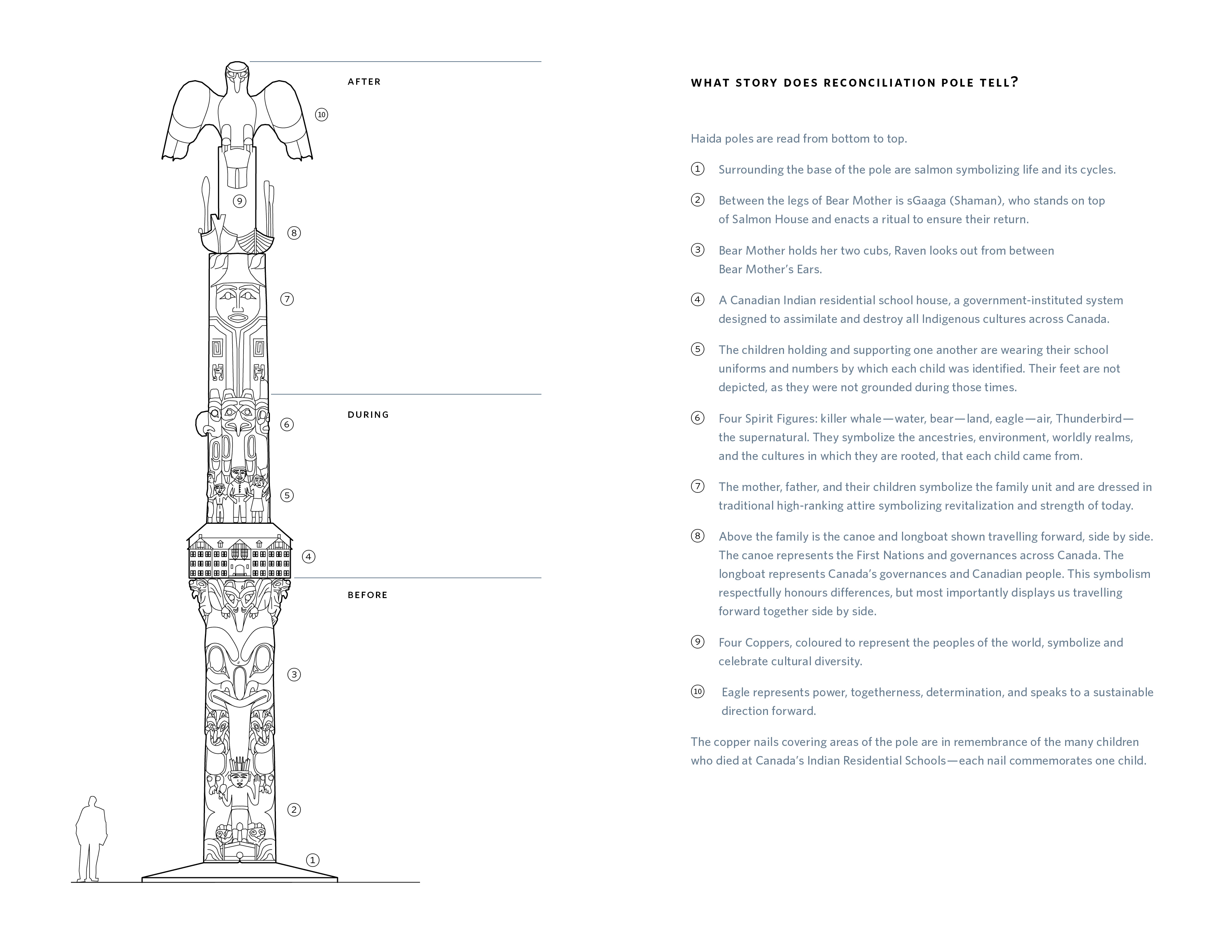

The pole shines with thousands of copper nails, each one representing a dead child. According to the TRC, at least six thousand children never returned from residential school — and the number may be much higher.

Many people contributed to the project by hammering nails into the pole. “For the [residential school] survivors, nailing in a nail makes them feel good,” Hart says.

“They remember their lost ones. It makes them think of that time…. Some people came by for days to hammer.”

“It's been really tough working on it, with more and more stuff about residential schools coming towards me all the time,” Hart adds. “It's quite emotional.”

Reading the Pole

Haida poles are read from the bottom up. The lower section of the Reconciliation Pole, featuring salmon, a raven and a bear, symbolizes the time before contact, Hart explains; “It represents our cosmos, our stories, our beliefs and ways.”

Then comes residential school. In an unusual and powerful artistic move, Hart has added two schools, carved separately and bolted on to either side of the pole, their straight lines standing out against the surrounding curved forms.

Above the schools stands a row of children created by Indigenous carvers from across Canada, including Coast Salish, Maliseet, Cree, Haida and Inuit artists.

“It’s about including Canada,” Hart explains. “Residential school happened all across Canada. My hope was to bring in other nations’ styles, to include their stories.”

Click on the image to see large version of "What story does Reconciliation Pole tell?"

Above the children are the parents of today, dressed in traditional Haida clothing and hugging their children in a tender embrace. “It’s about moving forward, learning to live together and love each other,” says Hart. “That’s happening now, our youngsters are starting to move past all this, starting to move ahead.”

Next up are two boats, a canoe and a longboat, also bolted on to the pole. “These are Haida boats,” Hart says. “But they represent all of us moving forward, travelling together into the future. Not just us Haidas but everyone, all Canada’s First Nations, all Canadians.”

“We are all together in this, it’s a blessing,” he adds. “We want to be part of Canada, we have a lot to give. We don’t want to be part of the destruction, the desecration, you can leave us out of that — we want fresh air and fresh water. It’s for everyone, not just us. It’s about working with Canada.”

On the very top of the pole is a massive figure of an eagle, its black wings outstretched. “It’s about power, determination,” Hart says. “It’s taking off into the future.”

A Giant Cedar

The Reconciliation Pole is one of the largest ever raised in BC: 17 metres tall, 1.7 metres wide at the base, 12 tonnes in weight. Hart helped select the tree, an 800-year-old western red cedar, on Haida Gwaii.

Three of the carvers who helped created Reconciliation Pole, in Haida regalia for the raising; left to right: John Brent Bennette, Gwaliga Hart and Jaalen Edenshaw. (Photo David Strongman)

“The first three we tried were rejected — not big enough,” he explains. “And it had to be near a road, to get it out.” The log was too heavy to be lifted by helicopter, and getting it onto a truck and down to Hart’s carving shed at Old Masset was a mighty undertaking. The crew began the carving on Haida Gwaii and finished it at UBC.

The pole now stands at the south end of Main Mall between Agronomy Road and Thunderbird Boulevard, looking north towards UBC’s new Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, set to open this fall.

It takes more than a village to raise a pole this important — it takes a whole country.