Musqueam Elder Larry Grant is Elder in Residence at the First Nations House of Learning, and Adjunct Professor in the First Nations and Endangered Languages program at UBC, where he teaches hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, the Musqueam language. As UBC installs Musqueam signage on campus, he talks about what the Point Grey area means to his people.

“It’s been a long time coming,” says Larry Grant, an 81-year-old Musqueam Elder. He’s standing by the Musqueam pole on University Boulevard, in front of the bookstore.

“It means a lot to us to have Musqueam recognition and acknowledgment on campus, in a very public space.”

According to their oral history, Musqueam have lived in Greater Vancouver, their traditional territory, for thousands of years. UBC, whose entire Point Grey campus sits on unceded Musqueam land, signed a memorandum of understanding with the Nation in 2006, and committed to aboriginal engagement in its 2009 strategic plan, Place and Promise. Fruits of this new relationship include qeqən (post), dedicated in 2016, and an agreement to add Musqueam signage on campus, which is now being realized.

The qeqən (house post) carved by Musqueam artist Brent Sparrow.

Vancouver is a Clearcut

Other than the area now called Wreck Beach, Grant points out that a century ago, the campus was forest; it was clear-cut in 1912 to make way for the university. “All of Metro Vancouver was forest,” he adds with a chuckle; “today, it’s the largest clear-cut in the southwest corner of the province.”

There were no permanent Musqueam settlements on campus, but there were villages all around the perimeter, including the present reserve to the south, where Grant grew up, and at Locarno Beach, to the northwest. “That is a huge, huge village site,” he says. “Trails criss-crossed the forest, from the river to the inlet. It was a place where we gathered our medicines, some of our foods, and the materials for making houses and canoes.”

The Musqueam also used the forest for ceremonial and spiritual retreat. “People would go there on their own, or sometimes together, and come to peace, come to terms,” Grant explains. “Very much like we take off for a few weeks and go camping somewhere and reflect on our life.”

Young people were trained in the forest, learning what plants were safe to eat and acquiring the discipline it took to live there. “It’s been a place of learning, of physical and emotional learning, for a long time. As it is today—it’s really interesting to see that.”

One of the nine bilingual street signs recently installed in 54 locations on the Point Grey campus.

A Strategic Site

“In the very first colonial days,” Grant says, “the campus was a strategic military spot.” In the late 1700s the warrior chief Capilano lived in a fortified site on the beach with the families of other warriors, mostly Musqueam. They fought battles from the area, and welcomed the first Spanish and English explorers, including George Vancouver.

“The lookouts were high up and the fortified site was on the beach. The families had a signal system watching for strangers coming from across the Salish Sea or up from Puget Sound.”

In 2011, UBC named a new house in Totem Park residence, q’ələχən, after this fortified site. A second house was given another Musqueam name: həm’ləsəm’, or transformation.

A Place of Transformation

“Our Transformer in the early times was named χe:l’s,” explains Grant. “He came along and helped people. The ones that didn’t respond to the encouragement were sometimes changed into animals or rocks.

One time a man settled at a spot just south of Wreck Beach by a natural spring and refused to share the water. So χe:l’s turned him into a rock, and also transformed the container he had into another rock. “There are a pair of rocks in that area that represent that,” Grant says.

The Musqueam chose the name həm’ləsəm’ to remind students of the importance of sharing. “Today at universities, you have to share all your resources, and if you don’t you might be transformed into a lump on a log,” Grant says with a chuckle, “in the sense that you won’t advance.”

Deer and Cedar

The campus was also home to elk, deer and black bears, Grant says. He recalls the last time deer were hunted here, when he was a teenager: “A few people come along and got them, and the community had a feast.”

There were also small mammals, including a lot of raccoons, which have become much rarer since the half dozen salmon-bearing streams were covered up with culverts. “The salmon attracts wildlife. Across Metro Vancouver, from here to Coquitlam, they covered over about fifty streams. It’s the real estate guys making millions on unceded land.”

The cedar to make canoes and longhouses came from on campus. Cedar bark was also used to make hats and clothing like capes which was crushed and woven into fine textile material. Cedar branches were used in spiritual ceremonies as well.

Bounty of the Beach

The Musqueam were not whalers but did hunt both seals and sea lions. They also harvested kelp along the beach; pre-contact, kelp was food, and as a young man Larry and his friends sold it to merchants in town, who used it to make food and medicine.

“We also gathered herring eggs; there were herring that spawned around the point area,” Grant says, pointing to an area near MOA. “Herring roe is a real delicacy, a very rich food, rich in oil, vitamins and nutrients.”

The Musqueam also fished from the beach for smelt—eaten right away—and salmon and eulachon, which were dried on racks. “They used to get mussels and clams around here too,” Grants says, “in my mother’s generation, around 1900.”

Do the Musqueam object to the nudity on Wreck Beach? “Oh no,” says Grant. “If people want to be without clothes, they can be. Traditionally, we would have been there in almost that state, because it’s so hot. And we didn’t have a Victorian attitude about the body, you have to remember that.”

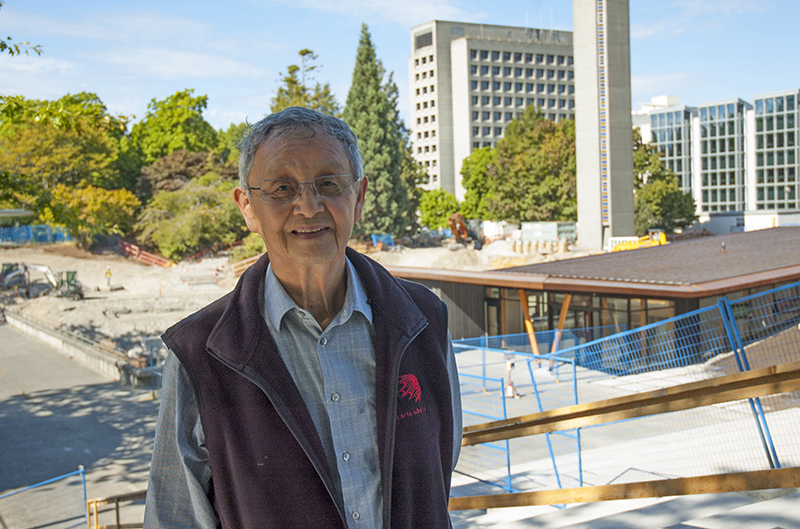

Elder Larry Grant stands in front of the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre in Fall 2017.

A History Shrouded in Shadows

The other part of campus that has become important to Grant is the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre. “They declared this the middle of campus, right here; the president’s office is right up there,” he says, pointing to the Koerner Library building. “They’re planting indigenous plants. To me, this has come to be a special spot.”

The Centre will be a place for former students and survivors of the Indian residential schools and their communities to access their records, and Grant is pleased that people can come here to research their families or learn about residential school issues.

Grant managed to avoid residential school, but many in the Musqueam community—including his wife—weren’t so lucky. What does the Centre mean, to Musqueam and other First Nations? “Hopefully it means that people will become a little bit more aware of all the acts of denial created by the Canadian government. And the Canadian government is an offshoot of the English parliament, and England is the heartland of freedom and democracy. Which had no problem subjugating indigenous people as part of their colonialist system.”

“How many Canadian-born people know anything about this? Very few. It’s a subject that’s not spoken of, it’s a part of Canada’s history that’s shrouded in the shadows…. If we have dialogue between international students that come from war-torn, politically subjugated countries, to this wonderful, free land, they can have a better understanding of that history.”

Grant notes the irony that the Centre sits in front of the I K Barber Learning Centre: “Barber made his fortune logging in the Kootenays, on unceded lands…. You know who the biggest benefactor of UBC is? It’s not Koerner, it’s not Barber, it’s not [Peter A.] Allard—it’s Musqueam! The billions of dollars of real estate that have been appropriated, that Metro Vancouver and UBC sit on. And if you can’t get that out of all of this, somebody has to wake you up!”

Grant apologizes for sounding angry. “It’s a challenge,” he says. “It’s a sensitive thing to talk about, and if nothing’s going to happen, you have to let it go. Not forget it, but not let it eat away at you. That’s the challenging part.

“I am bitter. But if I come across as bitter, you’re not going to listen to me, you’ll feel defensive. Either that or all of a sudden you’ll get guilty about something you shouldn’t have to, and you won’t listen to my story.

“And that’s so important—for you to listen to my story.”