Look back on the history of neighbourhood planning at UBC with Campus and Community Planning.

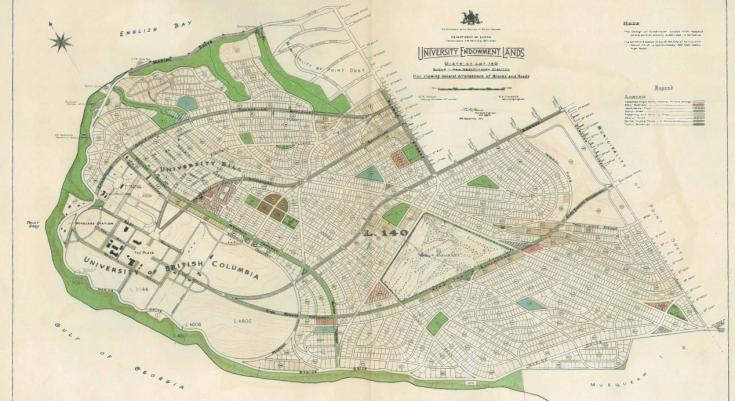

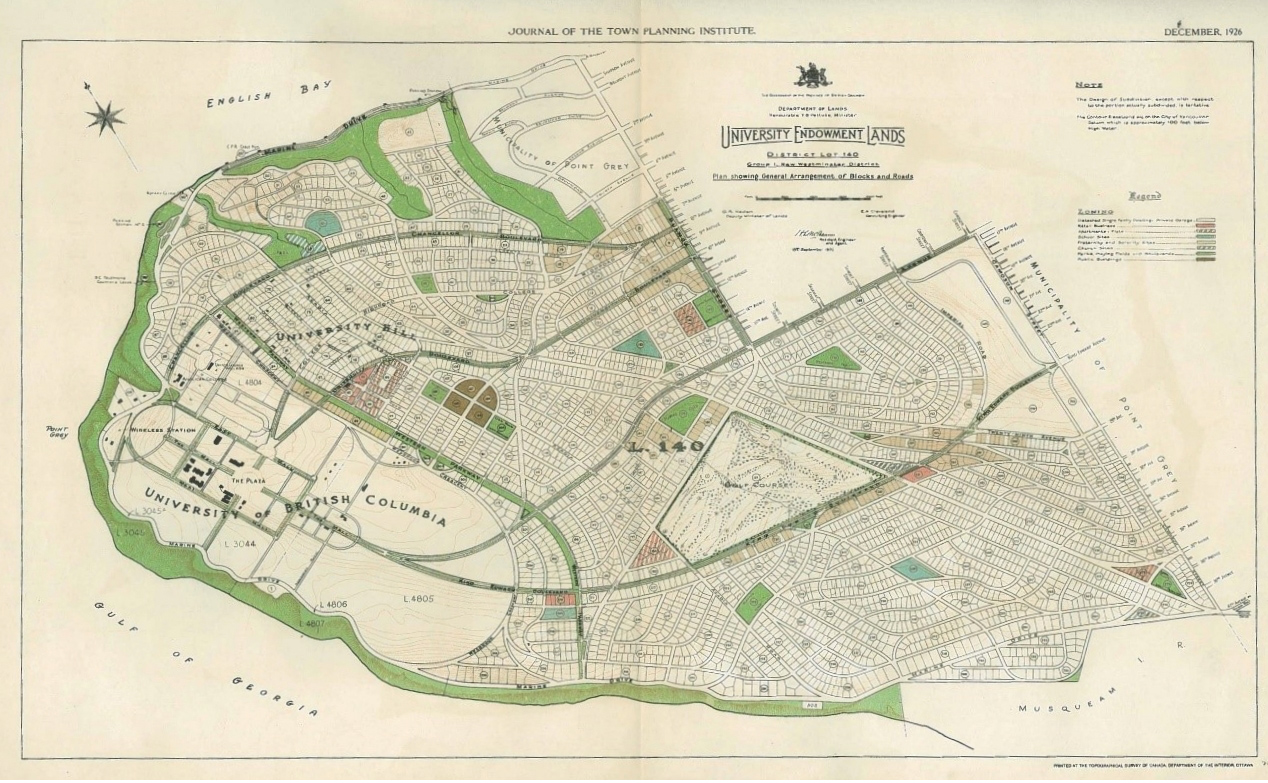

When Joanne Proft is asked why UBC uses some of its land for residential development, she often responds by showing a map from 1926. It shows an unbroken sea of roads and houses, covering all of Point Grey.

“That was the founding vision,” Proft, Associate Director, Community Planning at Campus + Community Planning, explains.

“The province set aside 3,000 acres in the peninsula as the University Endowment Lands, with the plan to develop housing to financially sustain UBC as a leading teaching and research university. The whole area that is now Pacific Spirit Park was meant to be a huge subdivision that would fund the university’s endowment.”

In the late 1980s, two major developments helped shape today’s UBC: the university created its first campus residential community, Hampton Place, and the province converted nearly two-thirds of the endowed lands into a regional park.

“Pacific Spirit Park dramatically shrunk the footprint of the endowment lands,” Proft says, “and housing on campus has been evolving ever since; we’re now building much more compact urban neighbourhoods, complete with community and commercial amenities so residents can live, play work and learn.” The original vision of a large tract of single-family dwellings has been transformed into a large regional park coupled with vibrant urban neighbourhoods and a bustling academic campus.

Six Neighbourhoods and Counting

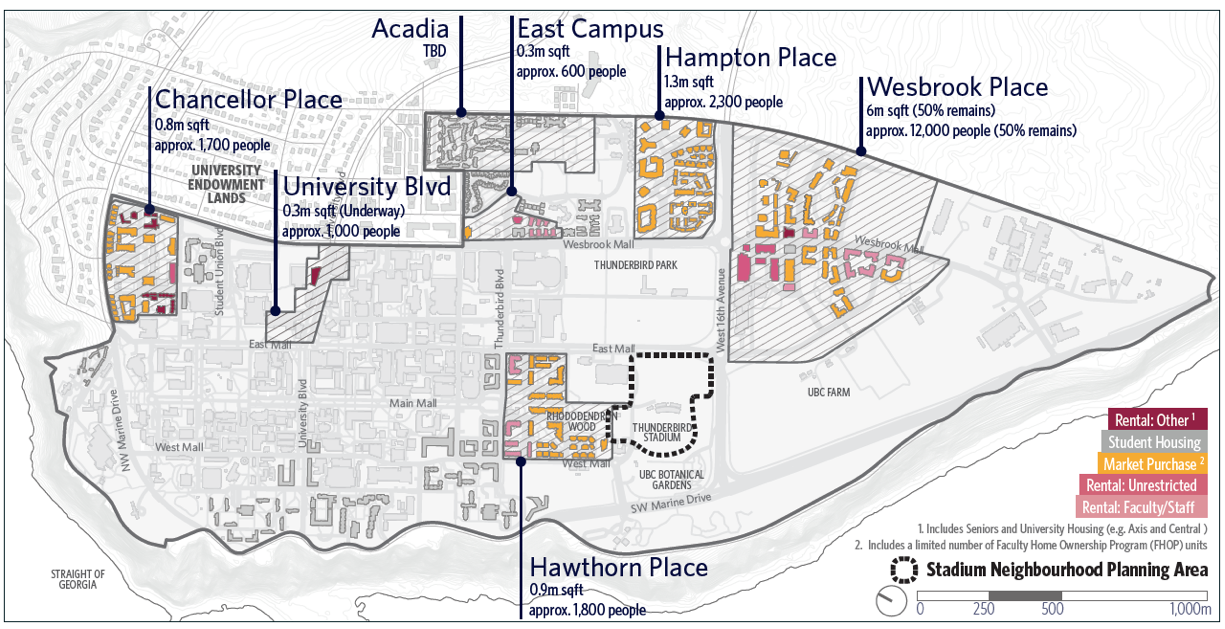

The Point Grey campus is now home to nearly 12,000 residents in six neighbourhoods: Hampton Place, East Campus, Chancellor Place, Hawthorn Place, University Boulevard and Wesbrook Place.

“Hampton Place is a stand-alone residential community, sort of like an island unto itself,” explains Chris Fay, Manager, Policy Planning at Campus + Community Planning. “It’s all condos; there are few rentals and no faculty, staff or student housing, no community amenities, no open or public spaces. Broader integration with the rest of campus, and the broader range of amenities and services—schools, restaurants, community centres—wasn’t part of the vision for campus when it was built.”

That all changed with the first Official Community Plan focused on residential communities, completed in 1997 in collaboration with the then Greater Vancouver Regional District. UBC’s changing vision reflected a shift across the region, towards mixed-use residential neighbourhoods, offering more choice in housing options and better access to shops, community services and green space. This plan shaped the next UBC neighbourhoods—Hawthorn Place, Chancellor Place and East Campus—all finished in the early to mid 2000s, and then Wesbrook Place, which begun in 2006 and is still being built out.

“Hawthorn Place used to be a parking lot,” says Proft. “The vision was to shift to away from an auto-oriented campus and use the space to build a real community. The Old Barn Community Centre has a cafe, and there’s a plaza and some rec space, including kid-oriented parks. It’s a lush green neighbourhood, which the residents really appreciate.”

Chancellor Place was designed to fit with the historic buildings in the Theological Neighbourhood. It has a more academic feel, and a transition to higher buildings as you move towards the academic core. It’s also more mixed-use, with some academic space.

A Tipping Point

“Hawthorn also has more and different housing types,” adds Fay, “both in terms of what the buildings look like and who lives there. It offered the first neighbourhood rental units on campus, and the first faculty/staff housing options.” These are rented at 25% below market rate, exclusively for UBC employees.

These trends were accelerated with Wesbrook Place, the biggest neighbourhood on campus.

“It was a real sea change,” says Carole Jolly, Director, Community Development at Campus + Community Planning. “With Wesbrook Place, we saw the campus community grow to a size that could support all sort of services: restaurants, banks, a grocery store, even a high school, and amenities like the big community centre. It reached a tipping point.”

“It’s a meeting place for residents,” says Richard Alexander, a Hampton Place resident who lived in Wesbrook for eight years and is in his sixth and final year on the board of the UNA Board. “There’s a village square, all the essential facilities you need: Save On Foods, a liquor store, food and drink and so on. To my mind the community works well, the business services are good.”

There are now almost 12,000 people living in the campus neighbourhoods. The long-term plans include three new developments: completingUniversity Boulevard, a central, mixed-use neighbourhood already being built that will include social and retail amenities including a pub, office space, and many recreational facilities; Stadium Neighbourhood, around Thunderbird Stadium,now two-thirds of the way through a neighbourhood planning process; and Acadia East, which will eventually be redeveloped—including new family student housing and a new neighbourhood. By 2041 the total resident population will have doubled, to 24,000 people.

Better Sustainability Practices

The plans for Stadium Neighbourhood are still being developed, under the direction of Michael White, Associate Vice-President at Campus + Community Planning. They have an even bigger emphasis on rental housing: at least 40% of the total, with the majority for faculty and staff. This meets the goals in UBC’s Housing Action Plan, which has already made UBC Metro Vancouver’s largest provider of workforce housing, with 685 units; this is projected to grow to at least 841 by 2021.

The growing community also allows for wise use of the land. “We want enough people to live at UBC for it to be a self-sustainable, vibrant, safe place where community well-being thrives,” explains Proft. “It’s becoming more of an urban space, with restaurants that open onto green spaces, and places for outdoor gatherings of all sorts. There’s a richer set of amenities for the whole community, and Wesbrook Village has become a destination for the retail needs of everyone on campus.”

The sustainability performance of the neighbourhoods has also improved steadily. “Wesbrook is the most advanced of the university’s neighbourhoods,” says John Madden, Director, Sustainability and Engineering at Campus + Community Planning; “it has a progressive rainwater management plan in addition to applying energy and water efficiency measures that lower utility bills and conserve resources. Higher levels of sustainability performance have been achieved by requiring all new development to be built to the standards of REAP, UBC’s own version of LEED for residential buildings, which has been very successful. The new Green Building Action Plan will continue to advance performance of neighbourhood residential buildings.”

“If you put up midrise and high-rise buildings, there are better opportunities for park space,” agrees Alexander. “I think the residents appreciate that.”

“To create a community of 25,000 people is a significant undertaking,” he adds. “When they look west they see empty lots and signs of building activity, construction equipment and piles of dirt and so on. The building continues; we’re all looking forward to seeing how it progresses.”